No, this is not about Joseph and his amazing technicolour dreamcoat of musical fame! It is about God’s creativity … and what we can learn about it from some things Paul says in his letter to his friends in Ephesus.

Thinking about this was triggered by a recent Facebook post by Claudia Beversluis of Calvin University in Grand Rapids, Michigan. This took me, with Charles Strohmer’s help, to one of his own ‘Waging Wisdom’ blogs. Then, out of the blue, came Matt Tuttlebee, an Irish friend of mine, and a ‘Bundoran Bible Reflection’ video that he made and posted on Facebook. During this time, I was also in touch with Alexandra Kingswell, another old friend, about her artistic designs.

It has all come together in a four-part harmony which I hope you will find helpful. (I don’t know who sings soprano and who alto or who tenor and who bass!)

- ‘God’s many coloured / many textured wisdom’ (Ephesians 3:10)

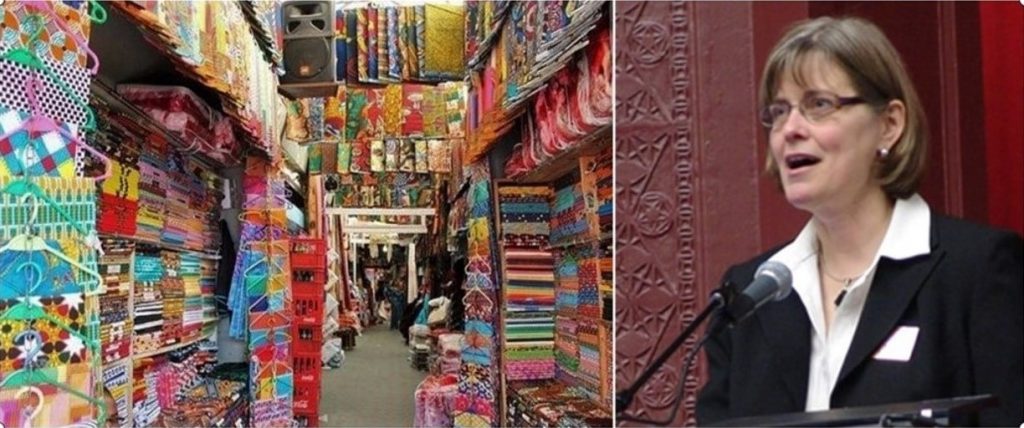

The story begins on June 7th with a sharing of a Facebook post by Tom Hoeksema, a good friend who was Head of the Education Department at Calvin College (now Calvin University) when I was a visiting teacher there on several occasions in the Noughties. What Tom had shared was a piece by Claudia Beversluis, a Calvin colleague, about the meaning of the Greek word polupoikilos and its significance for the current debate about racism.

Claudia says that she loves markets because they “are usually places filled with color, texture, smell, sound, chaos, and beauty”. So, she points out, when Paul writes in Ephesians 3:10 that “through the church the manifold wisdom of God will be made known”, the word polupoikilos translated ‘manifold’ is not an academic word. It is “a marketplace word, a word of the street, a word for colors and textures, and fabrics, and art”. It means many coloured or many textured!

She goes on to say that Paul’s wonder, surprise and delight can be heard in this passage. She imagines him exclaiming: “What we thought was in monochrome – look! It’s in purple, and green, and red and blue! This God has a different story than the one we thought was happening, and I, Paul – am alive to tell it!”

The wonder for Paul was the coming together of Jewish and Gentile Christians in one people of God. The wonder for us is of people from innumerable cultures coming together as the people of God. “Dividing walls of hostility” (Ephesians 2:14) are destroyed and, in this many coloured, many textured people of God, we are “being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives” (2:22).

2. ‘God’s handiwork / poem / masterpiece’ (Ephesians 2:10)

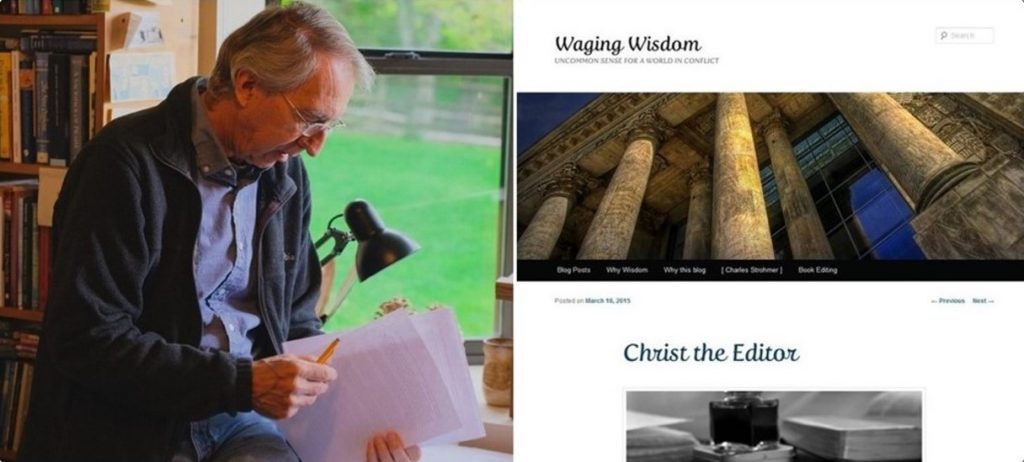

The story continues. Thinking about what Claudia had written triggered a memory for me. It was a recollection of reading or hearing at some time or other that where Paul says just a few verses earlier in Ephesians 2:10 that we are “God’s handiwork”, the translation could be “God’s work of art”. I mentioned this in a message to another good friend, Charles Strohmer whom you have met already in these blogs. He immediately sent me a link to a blog he had published five years ago and I realised that was almost certainly the source for which my aged memory was casting around.

Charles entitles his blog ‘Christ the Editor’ and he points out that the word translated ‘workmanship’ is poiēma. He says that this word was derived from a word for all kinds of craftmanship. In Homer’s time it was used for pieces crafted from metal and “it developed into a word that often denoted what we today would call artistic work, including the work of someone who wrote a book or a play. Plato and others after him also used poiēma especially of poetical works.”

Charles reflects on how great poems get written: “Just as every note in a musical score is significant, every word in a poem tells, and tells significantly. And it does not line up that way by chance or sloth. Poetry, with its compact, exact language and precise punctuation, may be the most carefully crafted and painstakingly written, and edited, form of communication. Poets will fight tooth and nail with a publisher over placement of a comma.”

He goes on to picture Christ as the editor working with us on the stories of our lives and replying after we have submitted a revised draft:

“Patience,” Christ the Editor responds. “You’re making good progress, but we’ve still got a few wrinkles to iron out. You have a tendency to get ahead of yourself or fall behind or forget about a change that’s been made. And you are still inclined to insist on keeping material from the old story.

“I know it’s slow and painful at times. I get that. But keep in mind that I’ve already been sending parts of your story around for reviews and, as you know, they’re being well-received. So hang in there. You want that masterpiece I promised, don’t you?

“So when will you have that next draft ready for me?”

3. God the Restorer / Master Craftsman

The story continues with me musing on what Claudia and Charles had written about these passages in Ephesians. I looked up the account in Acts 19 of Paul’s two-year stay in Ephesus and was reminded that it all ended with a riot which was started by “a silversmith named Demetrius, who made silver shrines of Artemis”. He called together “the craftsmen” for whom the worship of Artemis/Diana “brought in a lot of business” and also “the workers in related trades” (19:24-25) and soon the whole city was in an uproar.

So Ephesus was the home of skilled craftsmen whose trade had a “good name” (19:27). Paul himself was a tent-maker and it seems that he worked at his craft during those two years in Ephesus because he says in his later farewell message to his friends in Ephesus, “you yourselves know that these hands of mine have supplied my own needs and the needs of my companions” (Acts 20:34).

In the midst of these thoughts early on June 14th, I found myself watching and listening to an 8-minute video uploaded to Facebook that morning by an Irish friend, Matt Tuttlebee. In his ‘Bundoran Bible Reflection’ entitled ‘The Longing for Restoration’, Matt says that he loves a good restoration project and goes on to talk about the work he did for a friend in restoring a table, bench and chairs that had looked “tired and sad, rickety and brittle” and were “ravaged by woodworm and water damage”.

Matt then refers to Ephesians 2:10 about our being God’s handiwork. He says that God’s work in our lives can be painful because it will “expose faults of which we were not aware or didn’t want to face”. Restoring the table and chairs required abrasive processes such as planing and sanding the wood. God, the Master Craftsman, is also “patient and gentle with us” like the furniture restorer staining the wood and waiting for the paint to dry.

4. God the Inspirer of Art

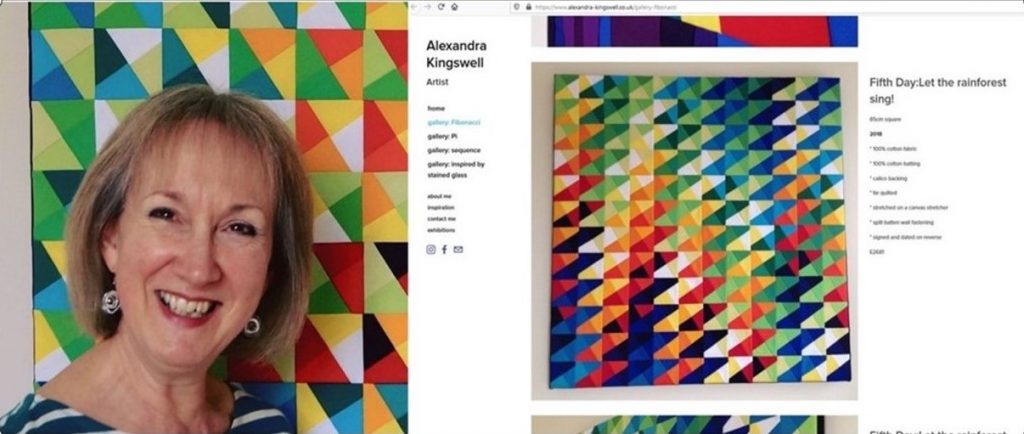

Through the days of this developing story, I was also in touch with another friend, Alexandra Kingswell, about her artistic work. When I first knew Alex back in the nineties, she was doing great work in designing the classroom materials that teams of teachers had worked on together and which we published for the Charis Project.

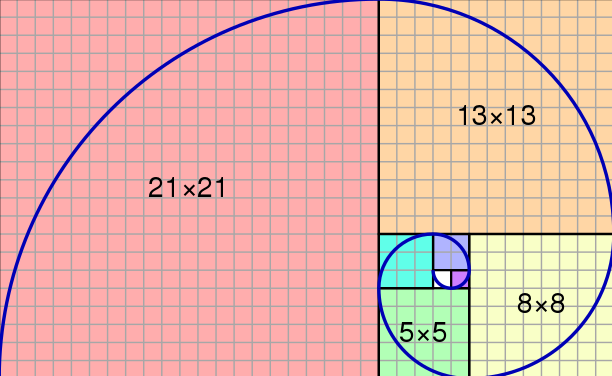

Since then, Alex has become a designer of beautiful one-off textile artwork in which, as she says on her website, she “explores the creative potential of number, proportion, sequence and colour”. A number of her works make use of the Fibonacci Sequence. I was in touch with her by email because I was then working on my recent blogs about the Fibonacci numbers and the Golden Ratio.

In one of her emails, Alex said that she loves “those (Old Testament) passages that talk of God designing the fabrics in the temple and His equipping of artisans with skill to do the work”. This took me to some Old Testament passages. Exodus 28 tells of skilled workers to whom God had given wisdom to make priestly garments for Aaron using “gold, and blue, purple and scarlet yarn, and fine linen” (28:5). 2 Chronicles 2 tells of preparations for building the temple and mentions “Huram-Abi, a man of great skill, … trained to work in gold and silver, bronze and iron, stone and wood, and with purple and blue and crimson yarn and fine linen. He is experienced in all kinds of engraving and can execute any design given to him. He will work with your skilled workers.” (2:13-14)

Alex’s work is that of a skilled artist and it surely displays the many coloured wisdom of God that Claudia Beversluis tells us about.

All of this applies at the level of the individual person who trusts Christ. God is at work in us as individuals to transform us into the image of Christ but we surely cannot stop with an individualistic account.

It is the whole people of God of innumerable cultures that is his many coloured work of art. In what Tom Wright in his recent ‘Undermining Racism’ talk calls “polychrome unity”, all the colours have their place as have all the notes in a piece of music, all the words in a poem, all the components of Matt’s beautiful upcycled table and chairs, and all the pieces that make up Alex’s textiles.

Let us pray.

Lord, you came as a man and worked for many years in the skilled craft of carpentry in Nazareth. In you all things hold together. Help us to use the creative gifts that you have given us in a way that attracts people to you and brings you honour and praise. Amen.

P.S. If you would like to be notified when new blogs are posted, please EITHER (1) email me through the contact address on this website OR (2) message me if you have come here via a link posted on Facebook.