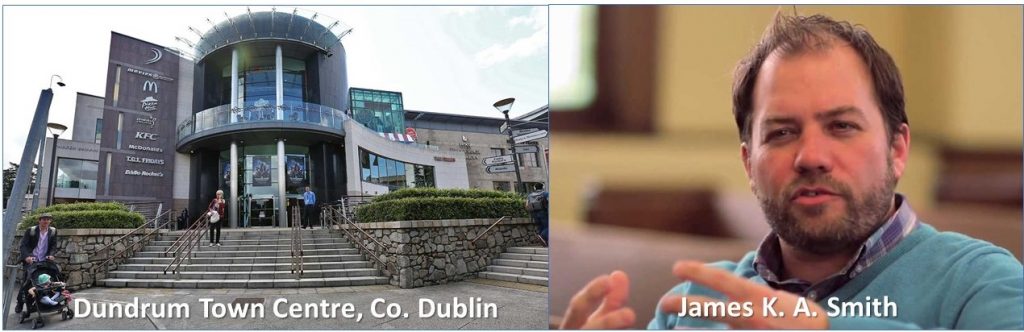

Imagine that we are alien researchers from Mars who have come to the strange world of Planet Earth to study the rituals and religious habits of its inhabitants. Imagine that we are going to visit one of our 21st century culture’s most common religious sites. This is what James K. A. (Jamie) Smith invites readers of his book, Desiring the Kingdom,[1] to do. Let’s accompany him as he approaches the site. It is not a church or temple … and yet it is!

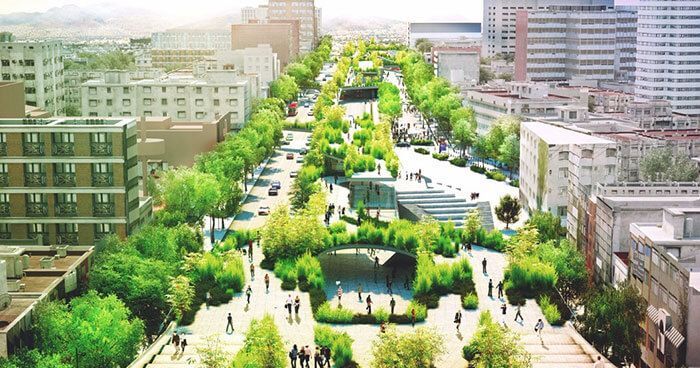

As we approach, we notice that the site is very popular. It is “throbbing with pilgrims every day of the week”. The entrances to the site are “framed by banners and flags, familiar texts and symbols” and just inside there is “a large map – a kind of worship aid” to help the novice to find the “various spiritual offerings”. The “regulars” don’t need the maps because they are “the faithful, who enter the space with a sense of achieved familiarity, who know the rhythms by heart because of habit-forming repetition”.

We notice the design of the interior of the site. There are windows on the high ceiling but none on the walls. This “conveys a sense of vertical and transcendent openness that at the same time shuts off the clamor and distractions of the horizontal, mundane world …(and) offers a feeling of sanctuary, retreat, and escape”. We find that it “almost seems as if … we lose consciousness of time’s passing and so lose ourselves in the rituals for which we’ve come”.

Like medieval cathedrals, the mall has “mammoth religious spaces … alongside of which are innumerable chapels devoted to various saints”. Instead of stained-glass windows, there is “an array of three-dimensional icons adorned in garb that—as with all iconography—inspires us to be imitators of these exemplars”. They embody for us “concrete images of ‘the good life’ …embodied pictures of the redeemed that invite us to imagine ourselves in their shoes”.

As we enter a side chapel, we are “greeted by a welcoming acolyte who offers to shepherd us through the experience, but also has the wisdom to allow us to explore on our own terms”. After a time spent browsing among the racks, “with our newfound holy object in hand, we proceed to the altar, which is the consummation of worship” where we find “the priest who presides over the consummating transaction … of exchange and communion”.

We leave “this transformative experience … with newly minted relics, as it were, that are themselves the means to the good life … something with solidity that is wrapped in the colors and symbols of the saints and the season”.

Like all good teachers, Jamie Smith is concerned to make the familiar strange and the strange familiar. He wants us to see the experience of the shopping mall with new eyes “in order for us to recognize the charged, religious nature of cultural institutions that we all tend to inhabit as if they were neutral sites”. Our desires are being shaped, our hearts are being formed, by the mall and “its ‘parachurch’ extensions in television and advertising”.

The point that he is trying to make is that human beings are worshippers. The question is not whether or not we worship but who or what we worship, who or what we love in our hearts. We have to have gods if God is missing from our lives.

Neil Postman says that consumerism is one of these gods. (He lists others, including nationalism, reason, science, and technology.) He says that the basic moral axiom of consumerism is expressed in the slogan “Whoever dies with the most toys wins”.[2] You are what you accumulate.

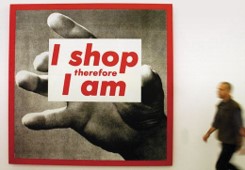

One of the most famous works of photographic artist Barbara Kruger proclaimed “I shop therefore I am”.

The god of reason says, “I think therefore I am” (cogito ergo sum). The god of consumerism says, “Tesco ergo sum”!

The God and Father of the Lord Jesus says that we are because he is.

Gracious loving Father, God who is love, please help us to always have the desires of our hearts shaped by you so that we may worship, serve and love you above all and we may help others to come to you and love you too above all. Amen.

P.S. If you would like to be notified when new blogs are posted, please email me through the contact address on this website or message me if you have come here via a link posted on Facebook.

[1] Desiring the Kingdom, pp. 19ff. See also here.

[2] The End of Education, p. 33.