Come walk with me into Psalm 42.

Hurting, really hurting

The first thing we notice is that the writer is hurting, really hurting.

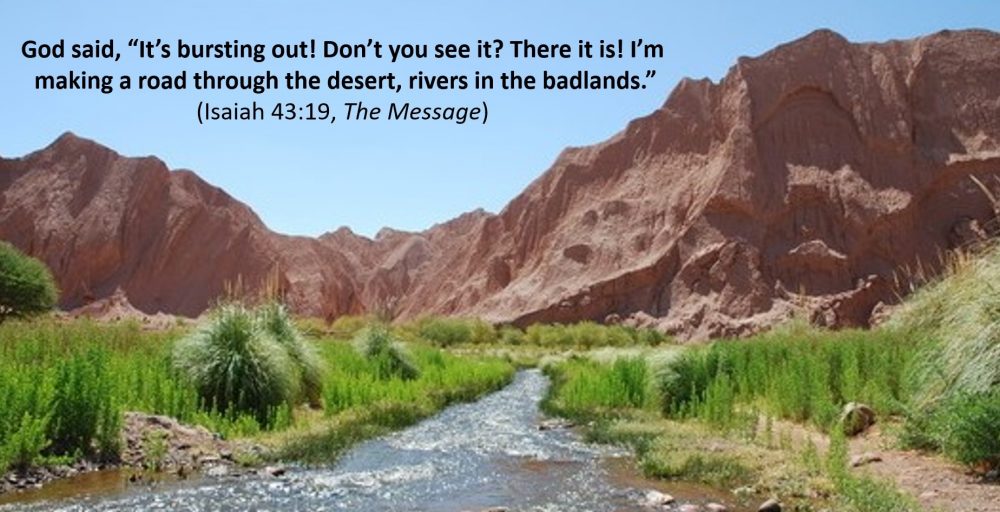

The psalm opens with the image of a deer: “As the deer pants for the water …” (v 1). This deer isn’t up to its elbows in a mountain stream – it is desperately searching for water in a dry place. The deer is suffering. Where can I find streams in this desert, rivers in these badlands?

As Eugene Peterson translates this psalm in The Message, the writer is “on a diet of tears – tears for breakfast, tears for supper” (v 3). He is “down in the dumps … crying the blues” (v 5). He says to God, “Your breaking surf, your thundering breakers crash and crush me” (v 7).

Some Christians would have us believe that our lives should be lived always on the mountaintop. I remember a chorus that I learned as a teenager that went: “I’m living on the mountain underneath a cloudless sky, / I’m drinking at the fountain that never shall run dry, …”. Is your sky cloudless today? Thank God if it is. It is like that some of the time. For some of us, it is like that more of the time than for others … but please don’t kid yourself that it will always be so! And don’t let others make you think you are somehow a failure if it is not for you a matter of always walking on the mountaintop.

It wasn’t so for Job, it wasn’t so for David, it wasn’t so for Jeremiah, it wasn’t so for Paul, it wasn’t so for Jesus! He wept, he was the “Man of Sorrows” who was “acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3)!

Questioning

The second thing we notice is that the writer is asking questions.

He is questioning deeply and even questioning God. Again and again he asks “Why?”

There are many today who ask us, ‘Where is your God?’ and if we find it hard to see him in our circumstances, we may begin ourselves to ask the same question, “Where is God?” How can this be happening to me? How can this be happening to the person I love so much? Why have you forgotten me, O Lord? Jesus, the Son of God, asked his Father that question as he hung on the cross!

Is it wrong to ask God questions? If we are asking humbly with a genuine desire to know, then I suggest that it is not wrong. It is all a matter of our motives, of the attitudes of our hearts. The writer says twice that his enemies are asking, ‘Where is your God?’ That doesn’t sound like a question that comes from a true desire to know or a humble heart that is open to learn.

As I read, watch or listen to the news, I find myself asking, “Why do bad things happen to good people? … Why do the wicked prosper?” The latter question was asked by Job (Job 21:7) and one translation puts it like this: “Why do the wicked have it so good?” Why, O Lord?

And yet, and yet …

The third thing we notice is that, in all this hurting and questioning, there is an “and yet, and yet”!

Hear Eugene Peterson again: “soon I’ll be praising again … He puts a smile on my face, He’s my God” (v 5) and “God promises to love me all day, sing songs all through the night!” (v 8). Tears in the night but also songs in the night – what Leonard Cohen would call a “broken hallelujah”!

It is not that the hurt has gone or the questions been answered – they are still there but they are accompanied by a hope that says God is there in the darkness and that one day we will see him and praise him.

There is a verse in Hebrews that goes like this: “We have this hope as an anchor for the soul, firm and secure. It enters the inner sanctuary behind the curtain, where Jesus, who went before us, has entered on our behalf.” (Hebrews 6:19-20)

The storms of life may toss us about but we can have a hope that is in Jesus who has gone on before us into the presence of the Father. That hope is an anchor in the storm. It is firm and secure and it holds us in spite of all that is washing over us, all those waves and breakers.

It is an assurance that God is there even when we are not living on the mountain, when we are deep in a dark valley.

A beautiful hymn by John Bell and Graham Maule of the Iona Community begins, “We cannot measure how you heal / or answer every sufferer’s prayer, / yet we believe your grace responds / where faith and doubt unite to care.” It goes on to talk of “The pain that will not go away, / the guilt that clings from things long past, / the fear of what the future holds”.

Let’s make the last four lines our prayer.

“Lord, let your Spirit meet us here / to mend the body, mind and soul, / to disentangle peace from pain / and make your broken people whole.”

P.S. If you would like to be notified when new blogs are posted, please EITHER (1) enter your email address in the box above ‘Subscribe’ on the ‘Posts’ page OR (2) email me through the contact address on this website OR (3) message me if you have come here via a link posted on Facebook.