A heart-warming story behind this picture will follow shortly but first I have a simple task for you. Take a few moments to think of a sentence that begins, “I know …”. Got one? Good!

The sentence you have thought of will probably fall into one or other of three main categories, three kinds of knowing.

The first kind of knowing is knowing-that. I know that the square of nine is eighty one … Helsinki is the capital of Finland … Nelson Mandela was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1993 … water usually freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit. This kind of knowing is factual knowledge.

The second kind of knowing is knowing-how. I know how to swim … ride a bicycle … change gear in a manual transmission car … make a sponge cake. (Oops, if the last of these is a claim I’m making for myself personally, it is very questionable!) This kind of knowing is skilful knowledge. It is acquired by doing, not simply by reading about it. I can be skilful at driving a car without knowing what is happening in the transmission when I depress the clutch to change gear.

Knowing-how is different from knowing-that. In an age when factual knowledge is available in an instant at the click of a mouse, skilful knowledge is becoming more important. That is not to say that factual knowledge is not important. Far from it, especially at the present time. Talk of ‘post-truth’ and ‘alternative facts’ had become common in recent years but the advance of the coronavirus has meant we have again become desperate to know the facts and we are becoming tired of spin.

The third kind of knowing is knowing a person, place or thing, knowing with a direct object. I know my grandsons, … the town where I have lived for several decades … the dolmen on the Irish farm where I grew up. This is relational knowing, knowledge by acquaintance.

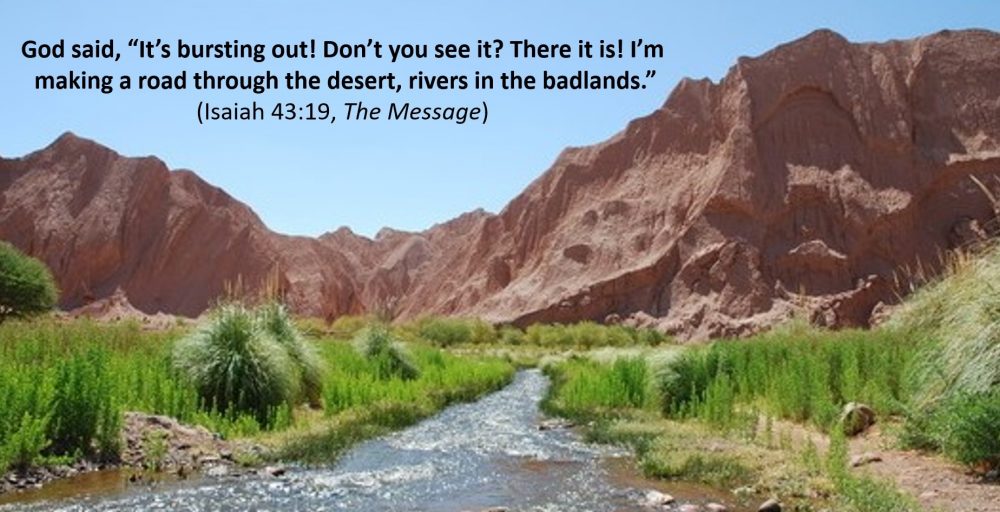

The importance of this kind of knowing has surely been brought home to us in these days of physical/spatial distancing. ‘Social distancing’ is a misnomer as the photo illustrating this piece shows so vividly. The photo is from a heart-warming newspaper article by Canadian Guardian journalist Daniel Brown[1] about a nurse and her grandmother, both of whom live on Cape Breton Island off the Atlantic coast.

Julienne Van Hul, 91, is in self-isolation at her home because of the coronavirus pandemic. As her grandmother has no internet, Stephanie McQuaid “had the idea of giving her a spare iPhone so she could use its FaceTime app to make video calls. … She bought a SIM card and phone plan … and then configured the phone to be senior-friendly and added some family members into its contact list. She cleaned the phone using lysol wipes and put it in a ziploc bag, then drove out to her grandmother’s home and left the phone package on her porch. Her grandmother retrieved it – making sure to wash her hands first. Then came the challenge of teaching Van Hul how to use the device through the patio window. McQuaid sat outside and used her own iPhone to help demonstrate, focusing exclusively on how to use FaceTime.”

Van Hul is now receiving FaceTime calls from various relatives. She has been “able to see one of her grandchildren who lives in Calgary, and she could share her thoughts on another grandchild’s new haircut”.

The three kinds of knowing are related. Some ‘knowing that’ is necessary for relational knowing for it would be strange to claim to know a person and not be able to state some facts about her or him even though the facts that we state may not be exactly the same as those stated by somebody else who also knows that person. At the same time, it is possible to make an in-depth study of facts about a person and still not be justified in claiming to know that person.

In a similar way, some interpersonal skills may also be necessary for relational knowing but they cannot be sufficient for it because we may know to some extent how to relate appropriately to a person without actually knowing that person.

Relational knowing cannot be reduced to either ‘knowing that’ or ‘knowing how’ or even to a combination of the two. Something more is required by way of a direct acquaintance with or immediate awareness of the person, place or thing that is known.

These distinctions among kinds of knowing are reflected in many languages. In French, for example, relational knowing is connaître while savoir is used for both ‘knowing that’ and ‘knowing how’. German distinguishes usages even further for it has different words for all three kinds of knowing—wissen (know that), kőnnen (know how) and kennen (know a person or place).

The Scottish and Northern English word ‘ken’ has its origin in kennen as in the folk-song ‘D’ye ken John Peel’ although it’s meaning is not limited to relational knowing. We talk of things being ‘beyond our ken’.

Irish Gaelic has the same word for ‘knowing that’ and ‘knowing how’ and a different word for ‘knowing a person, place or thing. ‘Tá a fhios agam gurb é Baile Átha Cliath príomhchathair na hÉireann’ (I know that Dublin is the capital of Ireland). ‘Tá a fhios agam conas snámh a dhéanamh’ (I know how to swim). ‘Tá aithne agam ar Bhaile Átha Cliath’ (I know Dublin)

The word used almost always in the Old Testament for knowing of any kind is yada’. This is the word used when intimate sexual relations are written about in terms of ‘knowing’ a man or a woman. The same word is used for knowledge of God. Knowing God is not merely an awareness of his existence but a recognition of who he is and of his demands upon the obedience of those who know him.

Part III of Handel’s oratorio The Messiah opens with words from the Old Testament book of Job – “I know that my Redeemer liveth”. It takes the form of a statement of knowing-that but it is also and perhaps centrally a statement of relational knowing.

Father God, help us to grow in relational knowing, being connected with one another and with the physical creation of places and things and, above all, in connection with you. In the name of Jesus who came into this world of people, places and things to reconnect us. Amen.

P.S. If you would like to be notified when new blogs are posted, please EITHER (1) enter your email address in the box above ‘Subscribe’ on the posts page OR (2) email me through the contact address on this website OR (3) message me if you have come here via a link posted on Facebook

[1] My grateful thanks to Daniel for giving me permission to use his photo.