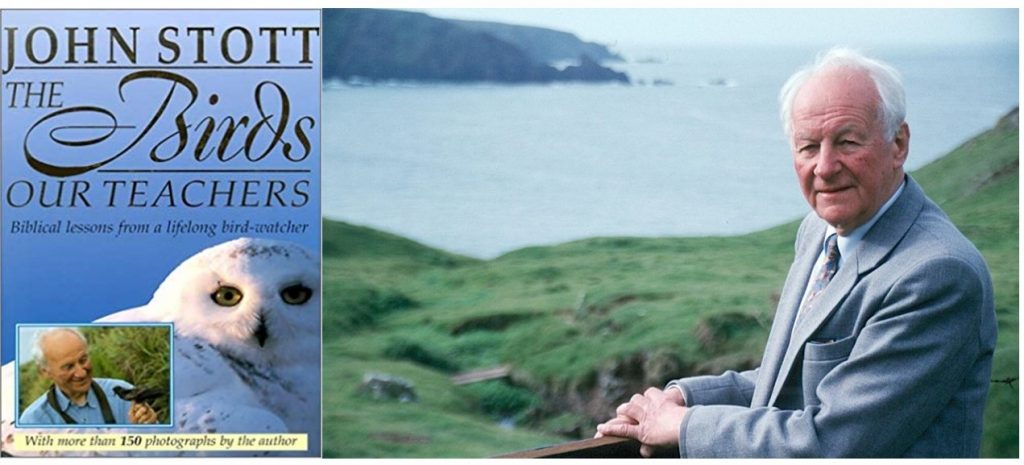

I guess many readers of this blog will have read one or more of the many books that the famous Bible teacher John Stott wrote during his long and influential life but have you read ‘The Birds our Teachers’?

In this unique book, John Stott introduces us to what he humorously terms ‘the science of orni-theology’ and he does so in eleven short chapters lavishly illustrated with more than 150 lovely photographs taken during his travels around the world.

Stott traces his lifelong love of bird-watching back to walks with his father in the country as a boy of only five or six years. On these walks, his father would tell him to shut his mouth and open his eyes and ears (p. 7). He finds “the highest possible authority” for his hobby in the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus tells us to “look at the birds of the air” (Matthew 6:26). He says that, in basic English, Jesus is telling us to “watch birds” and he points out that the Greek verb used means “to fix the eyes on or take a good look at” (p. 9).

The book combines the author’s personal stories with information about birds and with biblical themes in a way that should be of interest to both birders and Bible students alike. Each chapter focuses on a different bird (albeit not exclusively because many other birds are mentioned in each as well) and on a different spiritual lesson. It is therefore not a book to be read straight through from cover to cover but rather more of a coffee-table book to dip into and reflect upon, one chapter at a time.

My favourite chapter is one near the end of the book entitled ‘The Song of Larks: Joy’. As I read it, I’m transported back to an unforgettable experience that Val and I had some years ago when we were on holiday in the Black Forest region in Germany. We went up the Feldberg in a cable car and, as we stepped out onto the snowy slopes, a lark was ascending in the clear air and singing its heart out just above us. It was a moment of sheer joy for both of us as we walked near the summit of the highest mountain in Germany outside of the Alps.

The chapter is focussed on the lark and opens with Shelley’s ode that hails the “blithe spirit”. He goes on to talk about the songs of other birds including “the liquid bubbling trill of the Curlew’s spring song” (and I’m a little boy again walking in the callows[1] on my father’s farm!), “the resonant, explosive outburst of the Wren” and “the melodious flute-like warbling of the male European Blackbird” (p. 77). Another songbird I love to hear is the robin and, being an incurable early-riser, I’m serenaded each morning by one in a cherry tree beside our house … but that very territorial bird is the focus of another chapter (my second favourite) in which Stott talks about space and our need to preserve a “combination of colony and territory” and to avoid the extremes of isolation and total loss of privacy (p. 66).

Missing from the list of birds mentioned by John Stott is the wild goose. If I were to cheekily add a chapter to the book, it would be entitled ‘The Flight Formation of the Wild Geese: Interdependence’. I would go on to talk about the V-formation in which they fly. (Actually, it is often more like a J-formation because one leg of the V is longer than the other but the lessons to be learned are still the same.)

The lead bird works the hardest by breaking into undisturbed air. Drag is reduced and uplift is produced for the following birds and they expend twenty to thirty per cent less energy flying. As the lead bird tires, it drops back in the formation and another bird takes its place. The birds constantly communicate with one another by honking. Honking from behind is effectively encouragement for those in front.

In a study of the phenomenon of the V, Steven Portugal of the Royal Veterinary College in Hatfield found that the birds were not only placing themselves in the best place but also flapping at the best time to reduce the energy expended by the flock. He said, “They are just so aware of where each other are and what the other bird is doing. And that’s what I find really impressive”.[2]

If one goose becomes injured and has to land, a few family members will stay with it until it recovers. When it is ready to fly again they all set off and look for a new flock to join.[3]

In these days of life under the shadow of the coronavirus, we can learn, and indeed are learning, how we need one another. We are not independent, we are interdependent! And ultimately, we are all dependent upon God, whether or not we acknowledge it.

In Celtic Christianity, the wild goose was seen as a symbol for the Holy Spirit. God is not to be tamed. A Spirit-led life can be like a wild goose chase!

“Look at the birds, free and unfettered, not tied down to a job description, careless in the care of God. And you count far more to him than birds.” (Matthew 6:26, The Message)

Creator God, help us to sing for joy at the work of your hands and

to support one another as we seek to journey to wherever you are leading us.

Amen.

[1] Callows are a type of wetland found in Ireland. Most of the farm I grew up on was hilly but part was low-lying and flooded in winter.

[2] Nature, 16 Jan 2014, pp. 399-402.

[3] https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/natures-home-magazine/birds-and-wildlife-articles/migration/on-the-move/