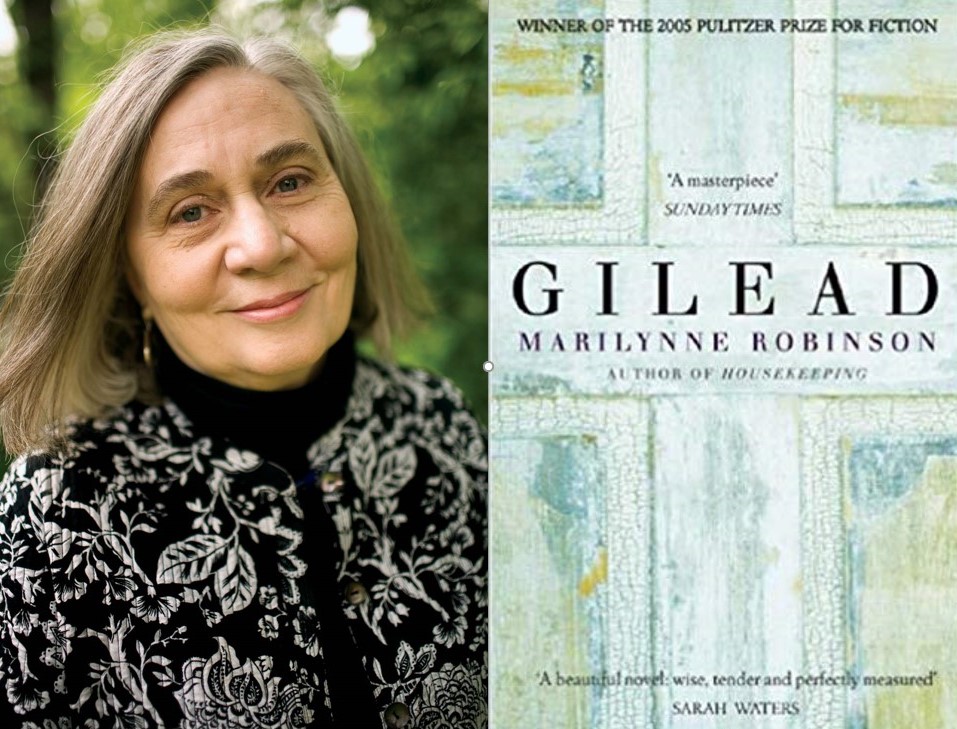

Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, the winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, was last year ranked second on The Guardian’s list of the 100 best books of first two decades of the 21st century. It is a staggeringly wonderful piece of writing and I have to confess that, although I feel I must write this piece about it, I am deeply aware that I cannot do justice to the extraordinary quality of the work.

The story

Gilead is set in 1956 in a small fictional mid-western town of that name in Iowa and it takes the form of a long letter by a 76-year-old Congregationalist pastor named John Ames to his six- or seven-year-old son. His first wife had died in childbirth and their infant daughter had also died soon after. In his mid-sixties after many years of loneliness, he met and married his second wife, a young woman named Lila (the subject of a later novel by Marilynne Robinson) and she gave birth to their son.

John Ames has been told that he is facing imminent death because of a heart condition so he sets about writing this story of his life for his son to read long after he has died. His grandfather had been a pastor in Kansas and had fought in the Civil War in the cause of the abolition of slavery. His father, also pastor of the Gilead church, was a convinced pacifist and this had led to a rift with the grandfather. John’s brother had studied in Germany and had become an atheist and had fallen out with their father. John’s lifelong and close friend, the minister of the town’s Presbyterian church, always referred to by John as ‘Boughton’ or ‘old Boughton’, features prominently in the story. So also does his son, ‘young Boughton’, who had brought disgrace on the family and left the town. Later in the story, he comes back home. John Ames struggles to forgive him for what he had done.

What some reviewers have said

“Gilead is much concerned with fathers and sons, and with God the father and his son. The book’s narrator returns again and again to the parable of the prodigal son — the son who returned to his father and was forgiven, but did not deserve forgiveness. … Robinson’s words have a spiritual force that’s very rare in contemporary fiction. … As the novel progresses, its language becomes sparer, lovelier, more deeply infused with Ames’s yearning metaphysics.” (Ali Smith, The Guardian, 16th April, 2005)

“Robinson’s prose is beautiful, shimmering and precise; the revelations are subtle but never muted when they come, and the careful telling carries the breath of suspense.” (Ellen Levine, PublishersWeekly.com)

“Robinson demonstrates the extraordinary in the ordinary. She shepherds us up to our own death and helps us face it with confidence. She validates our lives in places where we wonder if they have had any impact. … This book is an amazing unveiling of the truth of the Christian faith, barely hidden behind the curtain of human mortality. Robinson’s guided tour of the dusty, dry insignificant town of Gilead is a walk through the deepest of our human experience. She shows us how to celebrate life and God and appreciate every last thing about this life and the life to come.” (Fred D Mueller, Customer Review on Amazon website, 2nd April, 2017)

Some quotations from the book itself (you can find many more here)

“A man can know his father, or his son, and there might still be nothing between them but loyalty and love and mutual incomprehension.” (p. 8)

“Sometimes I have loved the peacefulness of an ordinary Sunday. It is like standing in a newly planted garden after a warm rain. You can feel the silent and invisible life.” (p. 23)

“People talk about how wonderful the world seems to children, and that’s true enough. But children think they will grow into it and understand it, and I know very well that I will not, and would not if I had a dozen lives.” (p. 76)

“Love is holy because it is like grace–the worthiness of its object is never really what matters.” (p. 238)

“There are two occasions when the sacred beauty of Creation becomes dazzlingly apparent, and they occur together. One is when we feel our mortal insufficiency to the world, and the other is when we feel the world’s mortal insufficiency to us.” (p. 280)

How and why has this book impacted me?

It’s opening sentences are: “I told you last night that I might be gone sometime, and you said, Where, and I said, To be with the Good Lord, and you said, Why, and I said, Because I’m old, and you said, I don’t think you’re old. And you put your hand in my hand and you said, You aren’t very old, as if that settled it.”

John Ames closes his letter to his son with these words: “I’ll pray that you will grow up a brave man in a brave country. I will pray you find a way to be useful. I’ll pray, and then I’ll sleep.”

The pages in between were for me a journey into my own inner life and the world of my memories as well as that of my present relationships with the Lord and with family members and friends.

Later this year I will be as old as John Ames was when he wrote this letter to his son. I certainly have fewer years left of this life than I have lived so far. My father was my age (and almost the age of John Ames) when he passed away. Yes, between my father and me there was often not only loyalty and love but also what Marilynne Robinson terms “mutual incomprehension”.

Although I’ve never been a church pastor, I’ve preached many a sermon. Like John Ames, I’ve often wondered about their impact.

In 1956, the time of the setting of the story, I was just entering my teenage years, a country boy living with my parents and young brothers on the family farm in rural Ireland. Everybody knew everybody else and every grownup knew everybody else’s family histories and their scandals. It sounds like Gilead, doesn’t it?

I never knew either of my grandfathers but my mother’s father, like John Ames, was married late in life to a younger woman. He was a God-fearing member of the Christian Brethren of whom my mother talked warmly, albeit rarely. I don’t know if there was anybody that he found it hard to forgive but I’ve known family members who have found forgiveness a struggle.

I have sons and grandsons whom I love dearly and for each of whom I pray a bright future.

Need I say more?

God of all love and all grace, help us to live in your Big Story and to walk with you to the end of our days. Amen.

P.S. If you would like to be notified when new blogs are posted, please EITHER (1) enter your email address in the box above ‘Subscribe’ on the right of this blog OR (2) email me through the contact address on this website OR (3) message me if you have come here via a link posted on Facebook.